Our Work

.

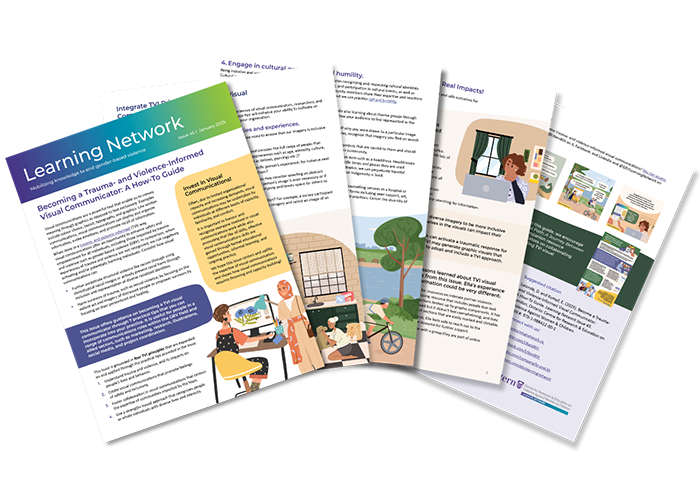

Becoming a Trauma- and Violence-Informed Visual Communicator: A How-To Guide

If you'd like to share the social media series related to this Issue, click here.

Visual communications are a powerful tool that enable us to convey meaning through graphics as opposed to text exclusively. Examples include colour choice, layout, typography, and graphics. Like written communications, visual communications can display and organize information, evoke emotions, and promote recall of information.

When done in a trauma- and violence-informed (TVI) way, visual communications offer an opportunity to enhance safety and empowerment for all individuals, including those impacted by trauma and violence such as gender-based violence (GBV). In comparison, when experiences of trauma and violence are not recognized, we risk negatively activating and/or potentially harming individuals. Consider how visual communications can:

Further perpetrate structural violence like racism through using stereotypical racial images or actively prevent racial harm through inclusion and representation of diverse racialized identities.

Harm survivors of trauma, such as sexual violence, by focusing on the violent act and imagery of distressed people or empower survivors by focusing on their personhood and healing.

Invest in Visual Communications!

Often, due to limited organizational capacity and increasing demands, visual communications may be undertaken by individuals at different levels of capacity, familiarity, and comfort.

It is important to honour and recognize everyone involved in visual communications work while also promoting that like all skills, effective visual communications skills are gained through formal educational opportunities, informal learning, and ongoing practice.

We hope this Issue centers and uplifts the expertise of visual communicators and shows how visual communications requires financing and capacity-building!

This Issue offers guidance on becoming a TVI visual communicator through 7 practical tips that you can incorporate into your practice. It is useful for people in a range of communications roles within the GBV field and allied sectors, such as marketing, research, illustrations, social media, and project coordination.

This Issue is grounded in four TVI principles that are expanded on and applied through the practical tips provided in the Issue:

- Understand trauma and violence, and its impacts on people’s lives and behavior.

- Create visual communications that promote feelings

of safety and inclusivity. - Foster collaboration in visual communications that centers the expertise of communities impacted by the topic.

- Use a strengths-based approach that recognizes people

as whole individuals with diverse lives and interests.

Integrate TVI Principles into Your Visual Communications Practice

The following practical tips are informed by TVI principles and the experiences of visual communicators, researchers, and survivors, particularly those working in the GBV field. Implementing these tips will enhance your ability to cultivate an encouraging and supportive environment for your audience and within your organization.

1. Select imagery that reflects diverse identities and experiences.

To represent the wide range of people impacted by trauma and violence, we need to ensure that our imagery is inclusive of diverse identities and realities. Inclusivity can be fostered when you:

- Include broad representation. When working on a resource, pause and consider the full range of people that may be impacted. Do you have representation of diverse identities and appearances such as age, ethnicity, culture, abilities, gender identity, weight, and visible expressions of identity (such as tattoos, piercings etc.)?

- Be conscious of imposing assumptions. If you are representing a specific person’s experience, for instance next to a quote, are you imposing your assumptions about their identity upon them? In the case of representing a quote or a specific person’s experience, you may consider selecting an abstract image of a person like a silhouette or line drawing. You may also ask if a person’s image is even necessary or if something else could represent what they are sharing. This avoids stereotyping and leaves space for others to envision themselves or others.

- Allow for interpretation. Are you leaving space for people’s own interpretation? For example, a survey participant described her experience of being othered and judged. You could use symbolic imagery and select an image of an eye behind a magnifying glass to portray judgment and scrutiny.

Consider the experience of Dylan (she/her), a visual communicator:

Dylan is working on a resource about supporting families who are experiencing poverty for a local food bank. The food bank said they support many different people, so Dylan included images of mothers and fathers together or separated, with a focus on diverse experiences of racialization. She also included common grocery items families may get like diapers, bread, etc.

How could Dylan use a TVI lens to enhance the inclusivity of the resource?

- Include diverse family structures representative of the 2SLGBTQI+ community

- Include animals as part of the family structure

- Include families that do not have children

- Include intergenerational families

- Include food items representative of diverse cultural cuisines and dietary requirements (such as gluten-free or plant-based)

2. Focus on empowering graphics.

People are impacted by the trauma and violence they have experienced, and they are also more than these experiences.When we only focus on one experience or dimension of identity, we limit the person and ignore the whole person. When discussing trauma and violence, we are already dealing with a heavy topic that is difficult to navigate. However, we can be mindful of increasing safety by limiting distressing imagery and sharing strengths where possible.Recognize strength and avoid harm through actions such as:

- Avoid violent imagery. Violent imagery can include images depicting abuse, weapons, or injuries. These images can be activating for survivors who have experienced violence. Instead, you can focus on the person, their emotions, and their healing.

- Use dark imagery sparingly. While dark imagery can be useful to portray feelings (such as burnout, depression, or anxiety), be aware of how often you are using these. Overuse of dark imagery can reinforce these feelings rather than fostering a sense of safety and healing.

- Focus on incorporating images that empower and encourage. For example, a point within an infographic reads: “Recognize how coercive control is impacting children, while also attending to their experiences of fun and happier times.” Instead of showing an image of an upset child, you could use an image depicting an adult supporting the child by doing an activity together.

Check it out!

This campaign identifies how assumptions about people with Down syndrome can become reality so rather than reinforcing stereotypes, we should focus on strengths, individuality, and independence. Access the video here.

3. Consider colour theory.

Different colours or colour combinations can be used to evoke certain moods such as urgency or distress. To evoke feelings of safety, you can:

- Create different moods. Experiment with various shades of colours or gradients, and what they represent. For an inviting and supportive experience, you may want to choose colours like earth tones (blues, greens) or pastels (pinks, purples) to convey comfort or calmness.

- Avoid harsh colour combinations. For example, bright red and bright yellow.

Not only can it be hard to read but it can also be stressful, distracting, and uncomfortable. - Recognize that colours can carry different meanings across cultures and social contexts. For example, purple is often associated with GBV awareness, while orange represents the National Day for Truth and Reconciliation. While you don’t need to avoid these colours, you should be mindful of their significance.

- Question your use of stereotypically gendered colours. Gendered colours such as pink for femininity and blue for masculinity can reinforce gender stereotypes and exclude diverse gender identities so consider where and why you are using those colours.

4. Engage in cultural awareness and humility.

Being inclusive and acknowledging people as whole individuals requires recognizing and respecting cultural identities. Cultural awareness can be gained through training, ongoing learning, and participation in cultural events, as well as through community partnerships and reviews for safety where community members share their expertise and reactions to visual communications. We will not and cannot know everything, but we can practice cultural humility. Ways to engage in cultural awareness and humility include:

- Set aside any assumptions. Recognize your own experiences while also learning about diverse groups through research and meaningful engagement with communities. This will allow your audience to feel represented in the work you produce.

- Avoid the use of stereotypes and offensive imagery. Ask yourself why you were drawn to a particular image or style, and be aware of how implicit bias may impact your choices. Also, recognize that imagery you find on search engines can sometimes be biased or limited.

- Be mindful of the meaning behind symbols. Many cultures have symbols that are sacred to them and should not be included in certain contexts or in resources created outside of their community.

- For instance, when representing Indigenous Peoples, avoid selecting an item such as a headdress. Headdresses are meaningful and sacred to many Indigenous communities with specific times and places they are used. Further, by including a headdress to broadly represent all Indigenous Peoples, we can perpetuate harmful stereotypes by not recognizing and centering the multiplicity of ways that Indigeneity is lived.

- Avoid images that reproduce colonial and imperial assumptions.

- For example, when discussing healing, you may lean into images of paid counselling services in a hospital or institutional environment. However, healing can come in many places and forms including peer support, art, storytelling, holistic approaches, the human-animal bond, and embodiment practices. Center the diversity of ways that people practice healing.

5. Integrate principles of accessibility.

Accessibility is needed because many people are systemically excluded from society through barriers that limit their full inclusion. For people with disabilities, for instance, this often manifests through ableism that positions people with disabilities as less than and contributes to their isolation. This isolation can lead to higher rates of violence amongst people with disabilities. Violence may also produce disabilities, such as traumatic brain injury , that impact how people access and store information.

Building universal and accessible design that is inclusive of all benefits everyone, including people

with disabilities and further groups that experience exclusion. Here are some ways that you can make your

designs accessible:

- Consider accessibility needs relevant to diverse communities. For instance, people in rural, remote, and northern communities may have barriers to access in downloading larger sized resources due to limited internet capacity so try to minimize the size of a resource or split longer resources into shorter ones.

- Centre the needs and expertise of people with disabilities. Invite reviews and feedback about ways that your visual communications practice can further meet the needs of the community.

- Follow accessibility requirements. Make sure you are fulfilling your duties under AODA (Accessibility for Ontarians with Disabilities Act) for those in Ontario and associated legislation in your region.

- Reduce visual clutter. Use white space to minimize cognitive load.

- Ensure your text is accessible by choosing an easy-to-read font. This can be either a sans-serif or serif font . Use decorative, cursive, or handwritten fonts sparingly as these can be difficult to read especially for longer sentences.

- Use a colour checker to ensure that your text is legible. To do so, copy the colour code of your font and the colour code of the background into a colour contrast checker to receive a grade. AODA requires that you comply with WCAG 2.0 Level AA standards.

- Include alternate text or “alt text” on informative images. These include diagrams, icons, and any graphics that add context to your resource, as well as social media posts. Mark images as decorative when they do not contribute meaningful information and only add to the appearance of the page.

- Try to include multiple formats of a resource when possible (e.g., written, visual, audio, video).

Check it out!

Vital Practices in the Arts is a resource guide for documenting, producing, and sharing arts and knowledge in ways that are accessible, collaborative, and disruptive. This guide is produced by Bodies in Translation: Activist Art, Technology, and Access to Life (BIT) with collaborating partners Creative Users Projects and Tangled Art + Disability. Access the guide here .

Making Accessible Media: Accessible Design in Digital Media is an open-access online course focusing on representation of disability in media, video captioning, audio transcription, described video and live captioning for broadcast, alternative text for image description, and tutorials on how to make accessible documents and presentations. Access the course here.

6. Remain curious.

Curiosity is key to applying a TVI lens. By remaining curious, we can increase our understanding of

trauma and violence, as well as ways to foster safety and inclusivity. To engage your curiosity:

- Participate in trainings on trauma, violence, diversity, inclusion, and decolonization.

- Build and maintain partnerships. Engage people from different communities and sectors (e.g., health, legal, disability, shelter). By doing so, you can gain knowledge and better understand nuanced situations to support you in your work.

- Don’t be afraid to ask questions. By asking questions, you become better informed and avoid any unintended negative consequences, enabling you to make more informed decisions on your own in the future.

- Keep up to date on trends and technologies. Over time, meanings of images and colours change so stay up to date on what is happening now. Use technology to support your TVI work such as enhancing accessibility and searching for more diverse imagery.

7. Practice self- and community-care.

TVI principles do not only apply to the content that you produce – they also can support you and your community! Visual communicators have their own experiences of trauma and violence, and work related to trauma and violence may produce vicarious trauma for visual communicators. To promote well-being and community care, you can:

- Celebrate and honour each other’s strengths and your own strengths.

- Recognize vicarious trauma. Watch for the signs of vicarious trauma and advocate for change at the structural level to decrease burnout and stress.

- Remember it’s a journey, not a destination. There will be times when we go in the wrong direction and need to be called-in to reassess and make changes. These call-ins are a part of learning and engaging in TVI visual communications. Be kind to yourself and to your growth journey.

- Engage in peer support. Peer support reduces social isolation and promotes empowerment.

Create and join communities of visual communicators.

TVI Visual Communications Have Real Impacts!

Engaging in TVI visual communications leads to more inclusive and safe outcomes for all involved, especially survivors of trauma and violence.

Consider the experience of a survivor of intimate partner violence who comes across visual communications that are not grounded in a TVI approach:

Ella (they/them) is searching for resources to understand their own experiences better and to support their efforts to heal and seek justice. They come across various resources, but the resources are long with lots of text. These resources feel overwhelming and difficult to follow.

Since they are more of a visual learner, Ella starts focusing on resources that include imagery. While easier to follow, Ella does not often see themselves represented in those resources as the people included are all white, able-bodied, and cisgender.

One resource includes an image with hands around the neck of a person who appears distressed. The image brings Ella right back to their own traumatic experience and they immediately close their laptop and stop searching for information.

Ella’s experience highlights the importance of including diverse imagery to be more inclusive and representative. The fact that they do not see themselves in the visuals can impact their engagement and sense of inclusion.

Additionally, the specific image of hands around the neck can activate a traumatic response for Ella, demonstrating how a focus that does not consider TVI may generate graphic visuals that can re-traumatize individuals. This underscores the need to adopt and include a TVI approach.

By taking the lessons learned about TVI visual communications from this Issue, Ella’s experience of accessing information could be very different:

Ella tries again to search for resources on intimate partner violence. This time they find an amazing resource that includes people that look like them with multiple sections broken up by graphic components. It has all the information they need but it doesn’t feel overwhelming, and they can jump between different sections that are easily marked and clickable.

Since accessing that resource, Ella feels safe to reach out to the organization who made the resource for further support.

Ella also shares the resource with a group they are part of online for survivors of GBV.

Share on social media!

Help us amplify these tips in support of more trauma- and violence-informed visual communications! You can access social media images to share here. Tag us @LNandKH on X, Facebook, and Linkedin and @GBVLearningNetwork on Instagram.

Click the thumbnail to view the full image

Authored by

Dianne Lalonde, Knowledge Mobilizer and Researcher, www.diannelalonde.com

Emily Kumpf, Centre for Research & Education on Violence Against Women & Children, Western University

The Learning Network Team

Margarita Pintin-Perez, Community Partnership Leader, Centre for Research & Education on Violence Against Women & Children, Western University

Jassamine Tabibi, Research and Knowledge Mobilization Specialist, Learning Network, Centre for Research & Education on Violence Against Women & Children, Western University

Graphic Design

Emily Kumpf, Centre for Research & Education on Violence Against Women & Children, Western University

Suggested citation

Lalonde, D. and Kumpf, E. (2025). Become a Trauma- and Violence-Informed Visual Communicator:

A How-To Guide. Learning Network Issue 45. London, Ontario: Centre for Research & Education on Violence Against Women & Children. ISBN #: 978-1-988412-80-1

All our resources are open-access and can be shared (e.g., linked, downloaded and sent) or cited with credit. If you would like to adapt and/or edit, translate, or embed/upload our content on your website/training materials (e.g., Webinar video), please email us at gbvln@uwo.ca so that we can work together to do so.